Going Deeper

Rosary in a Year Podcast

Ascension Press is doing a series on the rosary, called ‘Rosary in a Year’ which consists of a daily podcast.

You can access it here.

World Apostolate of Fatima ("Blue Army”)

History

In the early years of the Cold War, having discovered Our Lady of Fatima’s message, Msgr. Harold V. Colgan partnered with John M. Haffert to create the “Blue Army of Our Lady of Fatima”.

Members of this “Blue Army” were the spiritual force standing against the atheistic policies of the Soviet Union and their Red Army. They pledged to offer their daily sufferings and difficulties for the conversion of sinners, to pray the Rosary daily, to wear the Brown Scapular as a sign of consecration to Mary’s Immaculate Heart, and to practice the Five First Saturdays devotion.

The pledge, which Sister Lucia herself helped formulate, quickly gained popularity throughout the United States and soon became a worldwide movement, with between thirty and forty million people having signed the Blue Army Pledge.

In the early 1950s Msgr. Colgan, together with John Haffert, established the Ave Maria Institute on John Haffert’s farm in Washington, New Jersey. The farm served as the administrative center for sending and receiving new Pledge cards, handling correspondence, publishing Soul Magazine, and coordinating travel for the Pilgrim Virgin Statue. Around this same time they also purchased land in Fatima and built Domus Pacis hotel and conference center, which continues to house pilgrims and serve as headquarters for the International World Apostolate of Fatima.

John later donated his farm to the Blue Army, building a large shrine with a towering roof and 24′ bronze statue of Mary on the property. Today, this site is known today as the National Blue Army Shrine of Our Lady of Fatima, dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

The Blue Army of Our Lady of Fatima officially became the World Apostolate of Fatima and on October 7, 2010 was named a Public International Association of the Faithful. Today we serve as the Church’s official voice on the authentic message of Fatima.

For further information, please visit the World Apostolate of Fatima, USA website: https://www.bluearmy.com/

100% Orthodox Catholic Faith Formation

At the Institute of Catholic Culture, we dedicate ourselves to providing comprehensive education in the Catholic faith through an array of lectures, live seminars, and a wealth of resources. Our mission is to foster a deep and nuanced understanding of Catholic tradition and culture, equipping individuals with the tools for lifelong learning and spiritual enrichment.

We emphasize the importance of historical context, theological depth, and practical application, striving to enrich the lives of individuals and communities. By nurturing a robust and informed Catholic faith, we aim to support and inspire Catholics in their journey towards a deeper relationship with God.

For more details, visit Institute of Catholic Culture.

Pope John Paul II and the Faith/Science Dialogue

Pope John Paul II sought to bring the scientific world and the Church “into a new period of mutually respectful and creative interactions, one whose momentum and vision continue to guide us today.”

https://inters.org/reflection-on-John-Paul-II-science-religion

In the Holy Father’s 1988 letter to Rev. George Coyne, S.J., Director of the Vatican Observatory, he wrote:

“Turning to the relationship between religion and science, there has been a definite, though still fragile and provisional, movement towards a new and more nuanced interchange. We have begun to talk to one another on deeper levels than before, and with greater openness towards one another’s perspectives. We have begun to search together for a more thorough understanding of one another’s disciplines, with their competencies and their limitations, and especially for areas of common ground.

In doing so we have uncovered important questions which concern both of us, and which are vital to the larger human community we both serve. It is crucial that this common search based on critical openness and interchange should not only continue but also grow and deepen in its quality and scope.”

In response to Pope John Paul II’s desire for an ongoing dialogue between Science and the Church, in 2016, the Society of Catholic Scientists was founded.

Catholic priest and a prominent atheist scientist have a respectful discussion.

Telling the story of the late French Jesuit priest and scientist, the documentary, “TEILHARD: Visionary Scientist”

You can view the movie in its entirety on PBS here.

“The American Teilhard Association explores and shares the insights and cosmic vision of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, S.J. through scholarship, artistic expression, and educational programming.”

Please see https://teilharddechardin.org/

Evans, Joseph and Ngoc Nguyen. “The Virgin Mary as a Source of Strength, Comfort, and Hope for Asian Women: Our Lady of La Vang (Vietnam) and Our Lady of Health (Vailankanni, India).” Maria: A Journal of Marian Studies. Vol. 3, No. 1 (May 2023): 1-18.

https://www.marianstudies.ac.uk/maria-new-series-vol-3-1-may

Archaeological Find from Israel

Oldest Christian Church Floor

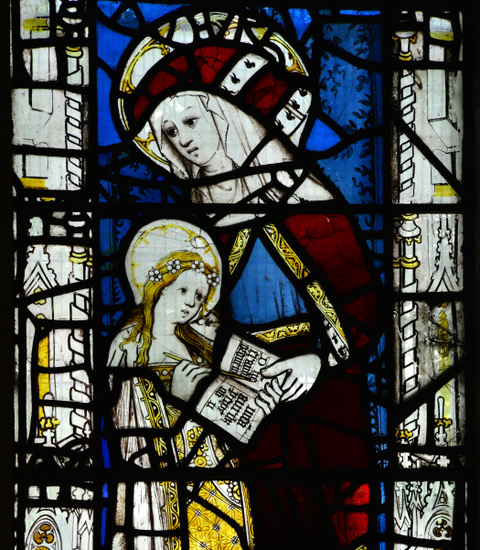

Stained Glass

The Illuminated Window: Stories Across Time is presented as a series of richly illustrated case studies of iconic stained glass, by distinguished scholar Professor Virginia Chieffo Raguin who was also a Contributor to the Rosary book.

An excerpt appears here from Book Review | Vidimus).

To understand stained glass windows, Raguin asserts we must first seek to understand their setting, their creators, their patrons, and the circumstances of their production. The chapter on Cologne Cathedral, for example, presents four phases of the cathedral’s glazing alongside a comprehensive discursive journey that encompasses the role of reliquaries in medieval society; the revival of twelfth-century typological themes during the Renaissance; the nineteenth-century Nazarene school of painting; and the expansion of Catholicism in America.

The chapters on Canterbury Cathedral also draws upon contemporary reliquaries and manuscript illustrations to explore the symbiotic relationship between pilgrimage and stained glass. At St Mary’s Church in Fairford, Gloucertershire, we learn how religious literature such as Nicholas Love’s The Mirror of the Blessed Life of Jesus Christ may have informed the subject matter of the windows. As Raguin writes of the parishioners, “their lives were dominated by family relation the negotiations of marriage and the joys and dangers of giving birth. They supported imagery that spoke to their world.”

Chinese: by Dr. John C. H. Wu,

Beyond East and West, 1951 (still in print)

At the family Rosary, I have often spoken to our children something to the following effect: “There is only one true Father, that is our Father in Heaven. There is only one true Mother, that is the Mother of God. Your Mommy and your Daddy are only the temporary representatives of the true Father and the true Mother. I appreciate the wonderful filial piety you have shown toward us, but always remember there is a higher filial piety, that towards God. Don’t depend on us, depend on Him. For we shall be taken from you sooner or later, but God will never leave you. Do not think that we have a big family, for however big the family may be, sooner or later we shall be scattered. In this world, there is no feast that does not come to an end. If, therefore, you want to see this family united forever, there is only one way to attain this end, and-that is for every one of us to be united with Christ. Whether we are together, whether we are separated, so long as we are united with Christ, we are united in Christ. There is only one separation that is real, the separation between Heaven and hell. If all of us belong to Heaven, then we are united in life and in death. If one of us belong to Heaven, and another to hell, then we are separated even in life. Physical togetherness means nothing; what is of value is spiritual togetherness.”

The entire book can be found here: Beyond East and West : John C.H. Wu : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive